Session 33 - The Canon of the New Testament

Introduction

By the end of the first century AD all the books that make up our New Testament (or New Covenant) were written and had reached their intended destinations. Many had circulated widely among the churches. However, there was no single recognised body of New Testament scripture that was known and used by all Christians. To complicate matters, so called "secret writings", with heretical teachings, were also circulating. Many believers only had the OT to go by; Gentiles may not have been inclined to use the OT.

What do we mean by "Canon"

The word "canon" originally meant a rod, or bar, used as a measuring instrument; it came to mean a "standard".

When used in relation to the Bible it describes the process and result of selecting those writings (66 "books") that are considered divinely inspired. Determining the canon of the Old and New Testaments (obviously separate exercises) was undertaken over a long period, by both Jewish scholars or early Christians.

We believe that, ultimately, it was God who decided what books belonged in the Bible. Hebrew believers recognized God's messengers and accepted their writings as inspired.

Verifying the Record

Writing of the Old Testament (which he, Paul, and others, relied on), Peter declared:

"...prophets were moved by the Holy Spirit, and they spoke from God" (2 Peter 1:21).

Speaking of his own experience (in his lifetime, on the Mount of Transfiguration):

"For we were not making up clever stories when we told you about the powerful coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. We saw his majestic splendor with our own eyes when he received honor and glory from God the Father. The voice from the majestic glory of God said to him, 'This is my dearly loved Son, who brings me great joy.' We ourselves heard that voice from heaven when we were with him on the holy mountain. Because of that experience, we have even greater confidence in the message proclaimed by the prophets. You must pay close attention to what they wrote, for their words are like a lamp shining in a dark place - until the Day dawns, and Christ the Morning Star shines in your hearts." (2 Peter 1:16-20)

Luke drew his Gospel account together from a variety of sources (Luke 1:1-4).

Paul said that that there were witnesses available in his day, who could corroborate facts of the Gospel (1 Corinthians 15:1-6). But what happened between then and the compilation of the NT corpus?

See also John's record:

"We proclaim to you the one who existed from the beginning, whom we have heard and seen. We saw him with our own eyes and touched him with our own hands. He is the Word of life. This one who is life itself was revealed to us, and we have seen him. And now we testify and proclaim to you that he is the one who is eternal life. He was with the Father, and then he was revealed to us. We proclaim to you what we ourselves have actually seen and heard so that you may have fellowship with us. And our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ. We are writing these things so that you may fully share our joy. This is the message we heard from Jesus and now declare to you (1 John 1:1-5)

Deciding what to Include

Before the New Testament canon was established, and put on the same level as the Jewish Scriptures, as divinely inspired, there was a variety of opinions among Christians about what writings should be considered authoritative. Some leaders were concerned that heretical writings might carry an undeserved authority. For example, a text called the Gospel of Peter, a product of a Gnostic group that claimed to possess a secret knowledge of God, circulated in parts of the world in the early centuries.

The process to finalize an agreed list of books took place gradually over the first centuries of the church. It took the following internal and external evidence into account.

- Was the author an apostle/did they have a close connection with an apostle (eg Luke, Paul)?

- Was the work accepted by Jesus Christ (eg the Law and prophets he cited)?

- Was the book accepted by the church at large?

- Was it read in churches and quoted as authentic in writings of early church fathers?

- Did it show consistency in terms of both doctrine and teaching?

- Did it agree with overarching rules of faith?

- Did it bear internal evidence of high moral and spiritual values that would reflect a work of the Holy Spirit?

- Did it edify people when read publicly and did it generate a positive heart response?

None of these criteria was used in isolation. Many books circulated claiming to be from the apostles. Some were accepted by groups of churches. The question was: what was actually inspired by the Holy Spirit?

Some books were debated:

- content of more interest to Jews than Greeks - James

- brief and specific - Jude

- seemed to be different in style from other material by the same author - 2 Peter

- private correspondence - 2 John, 3 John, Philemon

- uncertain authorship - Hebrews

...but were ultimate included.

Very early on, some of the New Testament books were recognized.

- Paul considered Luke's writings to be as authoritative as the Old Testament (1 Timothy 5:18; see also Deuteronomy 25:4 and Luke 10:7)

- Peter recognized Paul's writings as Scripture (2 Peter 3:15-16)

- some of the books were circulated among the churches with that level of authority (Colossians 4:16; 1 Thessalonians 5:27)

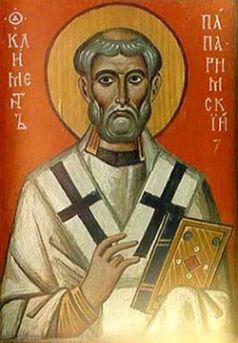

- Clement of Rome (95) mentioned at least eight New Testament books

- Polycarp (108), a disciple of John the apostle, acknowledged 15 books

- Ignatius of Syrian Antioch (115) acknowledged seven books

- Didache (first half of 2nd Century) supported Matthew, Mark and many other books)

- Hippolytus (170-235) recognized 22 books (A.D. 170-235)

- Irenaeus (185) mentioned 21 books

- Origen (185-250) accepted all except Hebrews, 2 Peter, 2 & 3 John, James & Jude

Clement - icon & my contemporary version

Important historical steps

The Canon of Marcion (140) included most NT books, however Marcion rejected the OT and his work was rejected by the early church as he was considered heretical on other grounds.

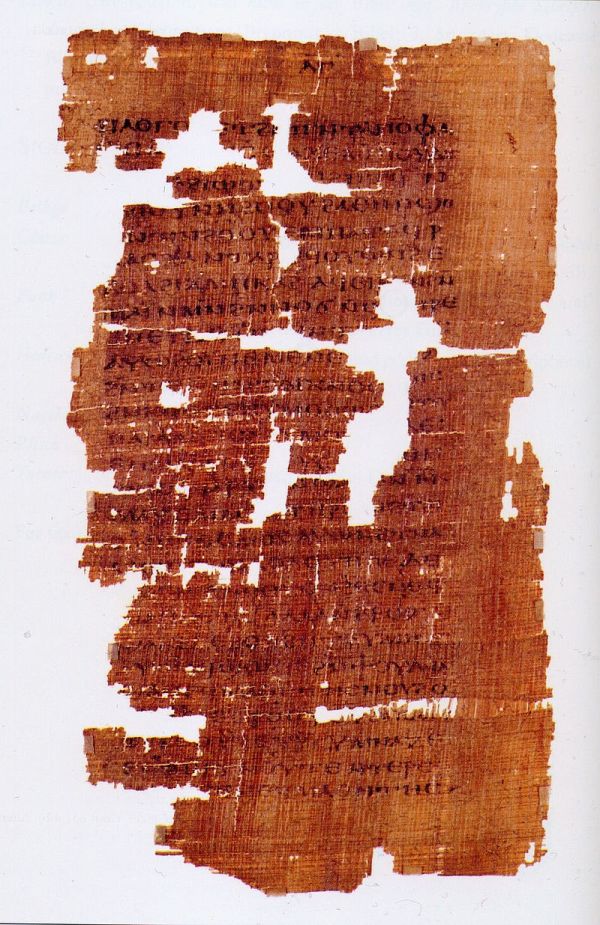

The Muratorian Canon, was compiled in AD 170. It included all the New Testament books except Hebrews, James, and 3 John.

In AD 363 (well after the Council of Nicaea), the Council of Laodicea agreed that only the Old Testament (along with one book of the Apocrypha) and 26 books of the New Testament (everything but Revelation) were canonical and were to be read in the churches.

The Council of Hippo (AD 393) and the Council of Carthage (AD 397) affirmed the 27 books we consider to be authoritative.

Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, seems to have finalized the issue on 7 January 367, when he wrote his annual "Easter letter" to the churches under his authority in Alexandria (North Africa). It was a landmark letter because it contained the same list of 27 books of the New Testament that are found in our Bibles today. So far as we know, Athanasius was the first Christian leader to compile a list of New Testament books exactly as we know them.

Here are portions of Athanasius' letter, in which he lists the books of the Old and New Testaments that he considered authoritative. (The English translation is the work of the late F.F. Bruce):

"Inasmuch as some have taken in hand to draw up for themselves an arrangement of the so-called apocryphal books and to intersperse them with the divinely inspired scripture, concerning which we have been fully persuaded, even as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word delivered it to the fathers: it has seemed good to me also, having been stimulated thereto by true brethren, to set forth in order the books which are included in the canon and have been delivered to us with accreditation that they are divine."

Athanasius then gave his list of Old Testament books and listed the 27 New Testament books.

"Let no one add to these or take anything from them.... No mention is to be made of the apocryphal works. They are the invention of heretics, who write according to their own will, and gratuitously assign and add to them dates so that, offering them as ancient writings, they may have an excuse for leading the simple astray."

Athanasius' letter was important because he was one of the most influential theologians and apologists of the church at the time. He had spent much of his life battling the Arian heresy, which denied the divine nature of Christ.

We shouldn't think of Athanasius as sifting through a stack of writings, and pronouncing this one as Scripture and the next one as unscriptural. He was merely recognizing and recording what amounted to the consensus of the churches.

Some of the books not listed among the 27 continued to be considered devotional writings, such as the Shepherd of Hermas and letters of Clement. But these also needed to be defined for what they were, so they would not be confused as having the same authority as the writings of the apostles and their colleagues.

The first church councils to approve the NT canon met in 393 at the Synod of Hippo Regius and in 397 at Carthage, in North Africa, some 30 years after Athanasius published his list. The councils endorsed what had already become the consensus in the churches of the West and most of the East about the extent of the canonical books of Scripture.

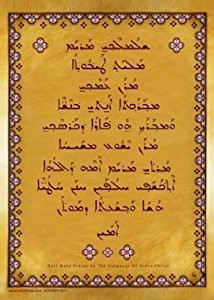

Jesus preached and taught in Aramaic; this was also the primary language of the first disciples.

Some oriental sections of the church (based in what are now Lebanon, Syria and Iraq) retained Syriac language New Testament books (and still do). Greek was the commercial language and in widespread use. Latin was the language of the empire. The church in the West spread the Word in (koine, or common) Greek, which was understood by many ordinary people.

Other Writings:

A host of additional writings emerged over time, some of which were of dubious value and authenticity. Other writings were the heritage of early church leaders, but did not make it into the final list, because (while helpful) they did not meet the criteria set out above. Some only emerged recently.

Gospel of Marcion (mid 2nd century)

Gospel of Mani (3rd century)

Gospel of Apelles (mid-late 2nd century)

Gospel of Bardesanes (late 2nd - early 3rd century)

Gospel of Basilides (mid 2nd century)

Gospel of Gospel of the Hebrews

Secret Gospel of Mark

Gospel of Peter

Protevangelum of James

Infancy Gospel of Thomas

Letters of Clement

Letters of Ignatius

Letter of Polycarp

Didache

Shepherd of Hermas

Epistle of Barnabas

Writings of Justin Martyr

Diatessaron of Tatian

Gospel of Truth

Gospel of Thomas (fragments found in 1945)

Gospel of Judas (fragments dated to 300 but only identified as such in 2000).

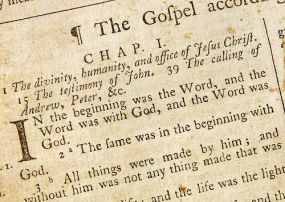

What about Chapters and Verses?

Stephen Langton (1155/56 - 1228), a Paris theological professor, was the first to make chapter divisions to help his work with Bible commentaries. In 1240, Cardinal Hugo of St. Cher published the first Latin Bible with the chapter divisions that exist today. While these divisions make it much easier to navigate the Bible than lengthy scrolls, it is important not to be limited by them.

Continue to enjoy the New Testament. Seek the enabling of the Holy Spirit to know both the text and the "Word made Flesh".